Merging an innovative modeling technique with old-fashioned sleuthing, researchers from the University of New Hampshire have shed new light on the mystery of pre-European archaeological monument sites in Michigan, even though most of the sites they’re studying no longer exist. The work, published recently in the journal PNAS, provides an important new tool in a field where many monuments have been lost forever to modern development.

The researchers — associate professor of anthropology Meghan Howey and associate professor of Earth and geospatial science Michael Palace, both of UNH, and Crystal McMichael of the University of Amsterdam and formerly a postdoctoral researcher with Palace — sought to better understand the roles of two different kinds of earthen constructions in Michigan. These burial mounds and circular earthwork enclosures, which generally date to the Late Precontact period of 1,000 – 1,600 A.D., are common across the eastern U.S. but have mystified generations of anthropologists.

“Understanding how such reconfigurations of the landscape affect societal development is a grand challenge for archaeology,” says Howey, who is the James H. Hayes and Claire Short Hayes Professor of the Humanities. “Our goal was to identify which spatial and environmental variables were important to the placement of these monuments.”

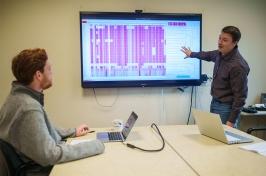

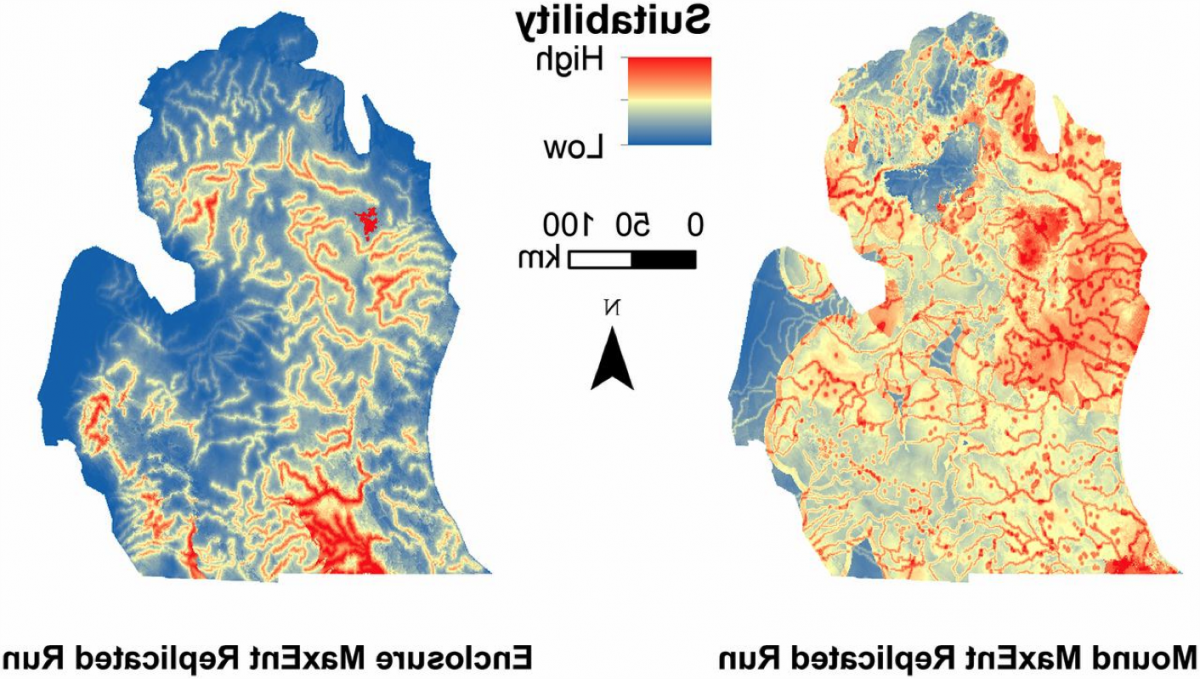

Utilizing a modeling technique called Maximum Entropy, or MaxEnt, borrowed from landscape ecology, the researchers determined that the two types of monuments occupied distinct niches in the landscape. Burial mounds were located near inland lakes, probably to serve local needs like food, shelter and community, while circular earthwork enclosures — some larger than football fields — were located near rivers.

“These enclosures became these shared ritual spaces. They were on rivers so they were accessible to multiple groups,” says Howey, adding that canoe travel along Michigan’s major rivers enabled the ancestral Anishinaabeg people to transport themselves and their goods long distances.

“Understanding how such reconfigurations of the landscape affect societal development is a grand challenge for archaeology.”

It was the researchers’ interdisciplinary approach that unlocked some secrets to these monuments, up to 80 percent of which have been destroyed. Howey, who has studied Late Precontact monuments in Michigan for more than a decade, pored through archaeological archives to create a database of mounds and enclosures documented in Michigan. Of the 60 enclosure locations and 261 mound locations her deep archival dive revealed, only an estimated 13 enclosures and 45 mounds exist today.

While using data that scientists call "presence-only" — working with just what you know to exist — may be challenging to archaeologists, "field biologists deal with that presence-only situation a lot," says Palace, a remote sensing and geospatial science specialist in UNH’s department of Earth science and Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS). "Just because you don’t hear a bird doesn’t mean it’s not there." He suggested harnessing the power of MaxEnt, inputting environmental values like topography, temperature, rainfall and distance from lakes or rivers from the existing and archival monuments to model "habitats" for additional monuments.

"When we turned this cultural process of monument building into a ‘species’, you could see the patterns pop," says Howey, one of the few social scientists affiliated with EOS. "It was really cool to show you can go to limited archival records and tell a new story about the past from these imperfect, limited datasets. It was this amazing convergence of ideas, going to that macro landscape ecology level."

Indeed, Howey recalls that it was McMichael — not an anthropologist but a paleoecologist — who first connected burial mounds to lakes and enclosures to rivers after reviewing the data. "Interdisciplinary work pulls you out of your tunnel vision," Howey says.

Palace, who studied archaeology as an undergraduate, echoes Howey’s interdisciplinary zeal. "I’ve immensely enjoyed the chance to work across disciplines and dip my foot in the archaeological waters," he says. The two will expand this modeling approach, supported by a NASA space archaeology grant to look at the rise of maize in Michigan inland lakes, to the entire Great Lakes region. It’s an archaeological area Howey calls understudied and underappreciated.

And their innovative use of MaxEnt for answering archaeological riddles in the absence of existing sites is gaining in popularity. "As development continues across the globe, and more and more ancient sites, including monuments, are erased by plows and heavy machinery, archival data may someday be the only surviving information," says Howey. "Modeling approaches like MaxEnt, which work well with limited data sets, will become an increasingly important tool for archaeologists to explore the past."

This research was supported by NASA Space Archaeology and an American Council of Learned Societies Digital Innovation Fellowship.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | Communications and Public Affairs | beth.potier@hwanfei.com | 2-1566